By Carl Bakay

Photos by the author, except as noted

As seen in the October 2004 issue of Model Aviation.

I am not a famous Indoor model flier. As have Dave Rees and Bob Aberle, who wrote “State of the Sport” articles before me, I have been active in all forms of the hobby since I was a kid growing up in New Jersey in the 1950s. Unlike them, I am a sport flier, a writer, and a newsletter editor, and I have worked hard at staying a novice when it comes to competition.

According to other writers, we take turns and detours in our lives that change us forever. This happened for me in May 1998. On a lark, I drove the 712 miles from New Orleans, Louisiana, to the East Tennessee State University campus in Johnson City, Tennessee, where the US Indoor Championships is held each year in a covered football stadium called the Mini-Dome.

I walked through the outer doors to a gymnasium hallway, complete with locker rooms and showers, and then through a second set of inner doors to the running track and playing field, which was 400 feet long and 116 feet high. I stood transfixed, as they say, and my mouth stood open as I watched these beautiful airplanes circle slowly and majestically over my head.

I was hooked then, and I am hooked now. But don’t believe me; to learn what is so great about “Indoor,” as it is called, I’ll quote Ron Williams.

“Indoor model building and flying is an innocent sport. There is little profit to be made, if any, in the commerce it engenders, though some enterprising indoor entrepreneur could find ways, I’m sure.

“Because it tends to be so low key and deceptively complex, it has never enjoyed the attention that noisier, more dynamic forms of modeling have received. The consequence is that there has never been enough information in any one place to get a good start with this part of the hobby.”

Therefore, Ron wrote and illustrated the first definitive how-to on the subject. His 1984 book Building and Flying Indoor Model Airplanes was a milestone then and a classic now, but I think it is out of print.

Returning to Johnson City a few years later as editor of the fancy Indoor News and Views magazine, numerous people came up to shake my hand and offered compliments, good wishes, and occasional war stories while I was trying to count the winds in my motor or time a flight.

But by day two, I learned not to be annoyed—that something larger was going on. I was part of a community.

As in all facets of our hobby, many types of models are flown in Indoor. Any Outdoor rubber-powered Free Flight (FF) design can be made lighter and smaller and flown inside. Heavy and strong are no longer requirements when there are no wind gusts or tree limbs in the way.

A good example of this is the Bostonian. These little 16-inch-wingspan cuties are flown outdoors with a 14-gram-minimum weight requirement and indoors with a 7-gram-minimum weight requirement. Although it’s hard to get down to 7 grams the first few times you try, flight duration goes from 2 minutes for an outdoor Bostonian to 5 and 6 minutes or more for the lighter indoor versions. In a place like Johnson City, with some of the “best air” anywhere, after all that time, your model will land about where it started.

It’s all about duration. As do the Scale models of the Flying Aces Club (FAC), some Indoor events award charisma points and appearance points, but the ability to outfly everyone else’s aircraft is the key to Indoor-contest success.

Origins—the Baby ROG: The first model airplane clubs started in the New York City area as early as 1907. The famous Frank Zaic flew in that city’s Central Park in the 1920s and 1930s. Balsa wood wasn’t used until roughly 1911, so most early models were made from pine, bamboo, and spruce. Rubber motors were cut from tire inner tubes, and plans were drawn on wrapping paper.

Our hobby can be clearly divided into two times: before 1927 and after 1927. That year a shy, handsome private pilot named Charles Lindbergh flew a highly modified and overloaded Ryan-built monoplane nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean. The effect on the youth of the era was nothing less than galvanic, and modeling as a hobby followed the groundswell. The number of kit manufacturers went from perhaps 20 in 1927 to more than 2,000 in 1928.

Let’s go back to modeling in the Depression years of the 1930s. We are in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and it’s wintertime. A group of clubs is making something called the “Philadelphia Model Airplane Association.”

They are giving out plans for a Baby ROG—not full-scale, of course. Part of your apprenticeship (if you want to join) is to scale up the plans on the back of some brown paper or, if you know a paperboy, a sheet of blank newsprint from the pressroom.

Then you have to build your own model, carve your own propeller, and get the aircraft to rise off the ground and fly indoors for 30 seconds. This is quite an achievement (especially if you use strips cut from automobile inner tubes to power it), although flights of more than a minute are possible. You then make it to the rank of “grease monkey” and can fly in Saturday contests.

John Walker wrote about his modeling origins with the Baby ROG in the July 1981 R/C Model Builder magazine. There were many versions of the Baby ROG, but it was a milestone in any of its forms. Why? Because it flew! Of all those Nickel Scale, Dime Scale, and quarter-scale models that the 2,000 kit makers offered, most would fly from your hand to the ground if they flew at all. The early clubs knew this and started you out with something realistic and flyable. Today we have something even better.

Begin With a Delta Dart: Bill Kuhl has to be the Delta Dart’s biggest fan. Read the following from his website and you’ll see why.

“The Delta Dart appeared in the April 1967 issue of American Modeler. It was designed by AMA’s [then] Technical Director Frank Ehling and promoted by Dick and Ruth Meyer.

“Why is it so great? With the exception of the motorstick, the AMA Dart is made entirely from 1⁄16 x 1⁄8-inch balsa strip. Some beginners’ models such as the Peck ROG utilize 1⁄16-inch square balsa, which although lighter, is difficult for the beginner to handle without breaking, and the structure will more easily warp.

“Also, the one-piece motorstick comes with the correct stabilizer incidence built in. The joints used at the tips of the wing, stabilizer, and vertical fin can be less than perfect and still be adequately strong because the covering material reinforces the joint.

“With materials donated by Sig, Dick and Ruth made up 300 kits on their kitchen table, some of which were taken by Frank Ehling to the 1966 Nats. Although some people thought the airplane too simple and heavy, kids found it easy to build and fly. It was thought that with the pointy wingtips, warps would have less effect because most of the wing area was closer to the center of the wing.

“Sig decided to sell the same basic airplane as a kit called the‘AMA Racer.’ The biggest change in the AMA Racer from the original Delta Dart is that the wing is movable, so center of gravity adjustments are easy. Another change is that the tailboom is made from spruce instead of balsa.

“Frank Ehling designed another airplane known as the “AMA Cub,” but it is sold by Midwest Products as the Delta Dart. According to the Sig catalog, this is the airplane that has been used in beginners’ promotions since 1968 and is the most-produced model airplane of all time.”

The Dart and various rise-off-ground (ROG) stick models are available in most good hobby shops and many toy stores.

It is a good idea to build your first few models exactly according to the instructions, and even a little heavier than needed, with extra glue joints and reinforcing fillets in the corners. This will help it survive all the banging around it is sure to do at first. You might take part in or help run an AMA make-and-take program.

A natural question is, What do I build after the Delta Dart? The answer is, Another Delta Dart. As you learn to build with lighter and thinner wood and replace the heavy plastic propellers with lighter balsa propellers, you will be building models that fly much slower and longer, and they suffer less damage if they hit something.

The world-class Endurance models shown seem to float through the air at walking speed, or slower, and are most in danger of being damaged by careless handling or a sneeze. But their owners will tell you they had to make several before they got it just right.

The best thing you can do on your second, third, and fourth Delta Dart is build with lighter wood, tissue covering, and a rubber motor at least twice as long as the loop that comes with the kit. Bob Warmann of the Chicago Aeronuts had a Delta Dart mass launch at the Midwest Championships and several flew up to the 94-foot ceiling.

Science Olympiad: The Delta Dart and the AMA make-and-take programs are great, but the participants are young—maybe 8, 9, or 10 years of age—and most do not continue with the hobby.

Sometimes, though, a parent will catch the modeling bug along with the youngster, and great things can happen. That is especially true with a new wave that has come along, and there has been nothing like it since the post-Sputnik catch-up days in education when I was a kid.

Few events have had as positive an effect on bringing young people into Indoor modeling as the Science Olympiad in our schools. Science Olympiad encompasses a host of biology, chemistry, physics, and engineering competitions, starting at the local level, and then moving on to state and national championships.

It uses a team approach, with an adult mentor providing guidance and support for a group of young people. The finale of a bridge-building exercise can galvanize an entire class when the time comes to hang weights on everyone’s creation to see how much they can hold before they break. The cheering, jeering, and just plain excitement are seldom seen outside of sporting events.

Science Olympiad has an event called The Wright Stuff, with apologies to author Tom Wolfe and his book of almost the same name. The rules for 2004 C Division required that the rubber-powered airplanes have 52cm (20.5-inch) wingspans and commercially available astic propellers no bigger than 24cm (10 inches). The motors could be any thickness or length but were limited to one loop of 2 grams maximum weight. The models had a minimum weight limit too; for 2004, it was 8 grams for senior and junior high, without the motor.

Are you confused by the units? Don’t be surprised if you see US and metric units mixed together like this. The Science Olympiad originators wanted to give students a taste of international science. Our country is one of the few that doesn’t use the metric system every day, although most scientists and some engineers use it all the time.

Indoor modelers use metric and US units interchangeably, generally depending on which one allows the use of whole numbers. It is easier to say 20 centimeters than 77⁄8 inches, and it’s easier to say your model weighs 10 grams than 0.3527 ounce. But rubber motors are sold in boxes by the pound, weighed in grams, and the length of the motor loop is in inches. You get used to it. But flight time is what it’s all about, and that is minutes and seconds the world over.

The Science Olympiad and its twin, the Technology Student Association, have exploded in popularity in the last few years. There are many different kits available for the Wright Stuff event, and more than a dozen plans available, from simple to elegant. The Cleveland Clowns webite even offers a tutorial video for sale. Many Science Olympiad and Technology Student Association mentors are active modelers who belong to clubs, and “invitational” Science Olympiad competitions have become common at club meets.

Bill Gowen and Gary Baughman are Science Olympiad mentors of multiple teams in the Atlanta, Georgia, area. Gary designed the Spartan, named after the school mascot, which is a robust model using 1⁄8 square wood similar to the Delta Dart and is designed to take a great deal of punishment from young hands, gym walls, and ceilings, and still fly.

Bill designed the Finny Plane, which uses 1⁄16 square wood, as does the Peck-Polymers ROG, and can be built to 8 grams without too much effort and puts in long flights as a result.

Both designers are active Thermal Thumbers of Metro Atlanta members, bringing many of their students to meetings and events. This is so popular that we “big kids” get into the act with such Science Olympiad variants as Senior and Unlimited Rubber.

Duration times here in the south are approximately 4 minutes, but a brilliant mentor in California named Cezar Banks designed his Leading Edge model with a wing so advanced that times exceed 6 minutes.

And I can’t forget Wayne Johnson, who had 7:37 when Bill Gowen hosted the Open Science Olympiad event in the huge Johnson City Mini-Dome. That is a long time for a flier—young or old—and the best thing is that being indoors, after all those minutes in the air, your airplane lands at your feet! People around you sometimes even break out in applause and cheers. Unlike when you are outdoors, your beverage is still cold and you haven’t been bitten by any bug—except that of Indoor flight.

If you have never made an Indoor model and you’d like to start with a kit, you can do no better than the Bambino or the Dipper by Ray Harlan. You can build two models from one kit. Another good choice is the Sci Oly 1 by Lew Gitlow, but I have not built it.

If you feel comfortable building from plans, Gary Baughman’s Spartan is at the top of my list. After being asked the same questions by so many people, he decided to write it all down. Gary offers a complete, hand-illustrated, step-by-step manual for building and flying the Spartan, plans included. Equal in quality but different in design is the Olympus by Don Slusarczyk.

One-Design Events: Don’t let contest names such as the “Midwestern States Indoor Championships” and “US Indoor Championships” frighten you into not going. Delta Dart and Double Whammy mass launches are held at the Midwestern States Indoor Championships and the last one down is the winner. The Double Whammy was featured in the November 1999 MA, and there was a follow-up article about how to make it more competitive.

The US Indoor Championships at Johnson City, Tennessee, features a P-24 Condor mass launch. The Condor is a great-flying model that was used for years at the U.S. Air Force Academy to teach flight principles.

The Thermal Thumbers in Atlanta, Georgia, have events for the Butterfly—a 7-inch wingspan Indoor ARF—and Laurie Barr’s Hangar Rat design.

If you are already pretty good at Outdoor Hand Launched Glider, Outdoor Catapult Glider, or FAC Scale Rubber, you can use the same skills in Indoor, except with lighter materials.

An added benefit of going to contests is that the larger meets often have vendor booths where they sell specialty Indoor items that are not available in your hobby shop.

Not into traveling? There are Postal events for many of these same models, in which you fly in your local gym and send your times in to compete with others from around the world.

Indoor Today—the Pennyplane, Easy B, and International F1D: The cover of the March 2002 Indoor News and Views was my idea but Steve Gardner’s artistry. Steve preceded me as editor, and he filled each issue with great plans and original illustrations. I arranged his artwork for four models—the Delta Dart, Pennyplane, Easy B (EZB), and F1D—from top to bottom on the cover of Issue #106.

All subscribers received a black-and-white version, but the original shows in striking color one way you can move up in building skill and flight duration by graduating from model to model, each more advanced than the one before. There are dozens of paths to take; this is just one. I have already covered the Delta Dart and Science Olympiad models, so let’s move on to a possible next step.

If you weigh a modern penny, it will be almost 2.50 grams. But before 1984, you got more for your money; a penny weighed 3.20 grams. That was settled on at the time as the Pennyplane model’s minimum weight. There were also restrictions of an 18-inch wingspan, a 5-inch chord, a 12-inch propeller, and other guidelines.

This makes it great for the step from Science Olympiad to serious Indoor competition. Anyone who can build a Finny Plane and do 4 minutes in a gymnasium can make a 4.0- or 5.0-gram Pennyplane the first time, and start doing 10-plus minutes in a large site.

My first Pennyplane weighed 5.0 grams, my second one weighed 4.1 grams, and my current model weighs 3.4 grams. It takes a great deal of practice, but you can expect to double your flight times by going from a 5.0-gram to a 3.2-gram airplane.

This design comes in two flavors: the original version and a Limited Pennyplane. Both have 18-inch wingspans and can weigh no less than 3.2 grams, but the Limited rules allow only a monoplane configuration and a sheet-balsa propeller with a 12-inch maximum diameter.

Indoor Model Supply makes a nice novice kit called the Time Machine. One of the two I built straight from the package did 6 minutes right off the building board in the 34-foot Tampa Armory. Building lighter from the same plans, it is possible to do 8 to 10 minutes or more. Those aren’t contest-winning times, but they give the builder a great deal of satisfaction and the confidence to move further along.

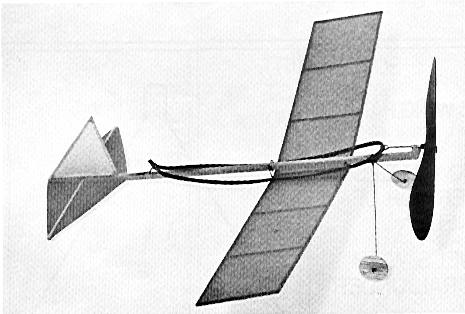

A possible next step is the EZB design invented by Wally Miller. It is a small 18-inch wingspan monoplane Rubber model with a 2-inch maximum chord and all-wood construction. Micro-X makes a nice beginner’s kit of this model and even provides the cardboard template around which the wing is built. Substituting lighter wood and smaller motor sizes on successive models will take your duration times into the double digits.

The attraction of the EZB is that beginners and experts can enjoy it, and beginners can become experts in a short time. The most popular contest design is the Hobby Shopper EZB by Larry Coslick, which, as the name implies, can be built from hobby shop wood and still weigh only .7 gram and fly for more than 20 minutes.

The bottom model on the cover is the most challenging and most amazing: the F1D. It is a world-class airplane, and the Time Traveler by Steve Brown has done 63 minutes on a tiny .6-gram rubber loop.

Others, who are braver than I am, say it is the most rewarding model since even your first F1D will fly longer than anything you have built previously. But if you are going to follow me this far, it’s time to take a detour and get out your wallet.

Stripping and Weighing Your Own Materials: Up to a point, you could build and fly Indoor with common supplies found in any good hobby shop or general model catalog. By this I mean that the propellers could be plastic and all the wood and rubber motors used could come in standard sizes.

However, for the Pennyplane, and even lighter models such as the EZB and MiniStick, you will want to strip your own wood and rubber and weigh the finished pieces more accurately than you have needed to before this. If serious competition is in your future, think seriously about a micrometer balsa stripper, a rubber stripper, and a precision pan balance.

The one-piece molded-plastic balsa strippers used for Outdoor FF models and use a #11 X-Acto blade aren’t good enough. Although they are fine for 1⁄8 and 1⁄16 wood sheets, they tend to split thinner balsa and give wavy and uneven cuts. I am not referring to fractions of an inch anymore, but thousandths of an inch. An EZB’s wing spars and ribs are .020-.030 inch (or 20-30 mil), and this requires a different approach.

Ray Harlan and Tim Goldstein offer quality balsa strippers with micrometer adjustments for the fine tolerances needed. If you are handy, there are plans available so you can build your own. These tools really shine when it comes to cutting many LE and TE spars the same thickness. They are also used to move a rib template down on the workpiece the same amount after each cut to give uniform ribs.

An added advantage is that by angling the wood or pushing the piece up in the middle to bow it, tapered spars and strips can be cut so more of the weight and strength is on the inside than on the tips. Many wing spars and almost all propeller spars call for tapered stock.

The cutting blocks use carbon-steel, single-edge razor-blade pieces or surgical-steel blades, which are half as thick as X-Acto knives and don’t split the wood. (You can still buy the older carbon-steel, double-edged blades, which are brittle and snap to a fresh, clean edge. Modern stainless varieties bend rather than break.)

Next comes stripping your own rubber to make custom-width motors. In Outdoor flying with multistranded motors, you change the motor’s cross-section by increasing or decreasing the number of strands. But with these light models, we are down to a single loop. One can do well in Science Olympiad and novice Pennyplane with 3⁄32-inch rubber strip (93-94 mil) from FAI Supply just as it comes out of the box.

Wind a few motors to the breaking point so you’ll know what 100% is. Practice winding to just fewer than maximum turns, finding the right motor loop length and the best trim for your model for that particular site. This could take several flying sessions or maybe a whole winter season.

After getting to the point at which no further improvement in duration is seen with a single size of rubber, buy your own rubber stripper. When you get a rubber stripper, you can simplify the rubber stock in your inventory and only buy 1⁄8- or 1⁄4-inch widths.

It’s not a waste either, because when you cut 1⁄8-inch rubber strip to get .085 inch for your Pennyplane, you can save the thinner piece for EZB or MiniStick flying. Keep all your stripped motors in plastic envelopes, and write the rubber batch, weight, and thickness on the outside with a felt-tip pen.

Last, an electronic pan balance that measures to at least .01 gram, and preferably to .001 gram, will be a welcome addition to your shop. Indoor plans give target weights for model pieces, as well as the whole, so you need to be able to accurately weigh a wing or a stabilizer to see if you are building in the right ballpark. Get in the habit of weighing everything and keeping good records.

Weigh your tissue and condenser paper and convert it to grams or ounces per 100 square feet to find the lightest available. Mylar plastic comes in thicknesses that are much lighter (and much stronger) than tissue coverings. For Duration Rubber flying, the best is a cellulose acetate film only 0.6 micron thick called OS film.

Apply these films by spraying the framework with 3M Super 77 contact cement and laying the work facedown on the film. Weigh the balsa you use in sheet and strip form and convert it to pounds-per-cubic-foot (ppcf) density. Indoor applications use 4-6 ppcf wood for most applications, with 8 and 10 ppcf wood for the more stressed propeller spars, wing posts, and motorsticks.

Cut your own sticks too. They will be much lighter, and you will save a great deal of money compared with buying precut spars. And of course, weigh all your motors and keep a record of that. I have two three-ring binders to keep my notes in, with dividers according to model class. One has building records and plans I keep at home, and one for flying I take to contests and practice sessions to keep track of what worked and what did not.

You are looking at $45-$75 for a micrometer balsa stripper, $160 for a good rubber stripper, and $50-$300 (or more) for a balance.

If you ask me if this kind of cash outlay is necessary, I will tell you about my brief foray into robotics. A reader wrote to one of the electronics magazines I subscribed to at the time and questioned whether an oscilloscope purchase was necessary. The editors answered that it was “the price of entry into the hobby,” meaning that you could do without it but not do well.

The accompanying table lists some motor choices to get you started, whether you choose a kit version, plans, or build from scratch. Each kit comes with full-size plans and complete instructions, so the kit could be your first effort, with lighter, more advanced models from the plans provided as a next step.

Always build several of the same design, because each model will be better and different from the one before. Indoor fliers seldom tell you how many of a particular airplane they have brought to a contest, but they will tell you that they have six or seven propellers, three wings, two tails, and four motor sticks.

This advice goes in spades for motors. You might cut some 62, 64, and 66 mil rubber and have it ready to tie into different-size loops at the contest, stored in carefully labeled envelopes or plastic bags.

Some of the competition motors in the table are described by weight rather than thickness. That’s because the rubber strip’s thickness and density varies from batch to batch, so weight is much more constant than size. Another reason is that weight indicates the total energy potential that can be expected from a motor.

The Future of Indoor: Some in the Indoor community, fine people though they are, would make this a short section because they say there is no future to Indoor modeling. Participation decreases each year, and there will be no one to fill the ranks as the great ones pass on to that great site in the sky.

That is baloney (as we used to say in New Jersey, where we ate a lot of it). As editor of Indoor News and Views, I’ve seen the subscription rolls climb from 550 when I started two years ago to more than 700 today.

Jim Buxton, Dave Linstrum, Bud Tenny, Don Ross, Bob Warmann, John Worth, and many others write about Indoor FF and contribute articles and columns, so we get our fair share of coverage.

I saw 10 Juniors and Seniors at the last contest—many from Science Olympiad beginnings—and a few already flying at a world-class level. Sure, the great Doc Martin passed away, and with it his Miami Indoor Aircraft Model Association Indoor club, but the Florida Flyers have emerged like a phoenix from their own ashes, thanks to the efforts of Bill Carney in Jacksonville and others. To prove it, they just held a successful meet in the Tampa Armory. I was there, and it was a hoot.

The fastest-growing segment is indoor micro-RC. Such pioneers as Bob Wilder, Dave Robelen, and John Worth are at the leading edge of incredible growth in this area of the hobby.

RC components have shrunken in size so much in the last few years that any small, light, electric-powered FF model can be modified and flown successfully. Open to debate is how indoor electric RC will be compatible with classic pure Rubber models.

The answer has to be equal but separate. Except for the lightest electric-powered models used in AMA events 221—FF Electric Power—and 627—Indoor Electric Duration (and even inclusion of these is at the contest director’s discretion)—everyone will be happiest if rubber and RC keep their separate ways, just as all good contests are separated into “heavies” and “lights” flying in different time slots.

We are seeing what the future holds with the introduction of smaller and lighter receivers and servos, geared pager motor drives weighing a gram or less, and LiPo cells that double and triple flight times. But the innovations are not limited to radio; carbon-fiber rod and tubes are standard building materials now, as are Depron foam sheets and Mylar and polyester covering films.

Bill Gowen’s composite Carbon Copy, a Hand Launched Glider, uses carbon-fiber rod and tough Mylar covering, and it wins.

Tungsten wire used to be the main bracing material for ultralight F1D models, but the current trend seems to be more toward unbraced wings and motor sticks. Instead of tungsten-wire rigging, the pieces are reinforced by laying down carbon and boron fibers and running a tiny amount of CA along the whole length for stiffness. Laurie Barr of England uses boron fiber on four sides of his hollow motor sticks, and he says they come out “as stiff as a pool cue.” The fibers are so thin that the weight penalty is small.

Florida Flyer Jake Larson is famous for his balsa-sheet Scale models, which he often converts to electric-powered FF aircraft. Now he is into doing the same thing with foam sheet. Although the foam is not as strong as balsa, his airplanes are so light that it doesn’t matter. He brought quite a selection to the Tampa Armory, and they all flew well.

We will see more and more of all these new materials and techniques in the seasons to come.

Perhaps the best thing for our hobby in the future is the growing list of supplies and information available on the internet. No matter what your interest or specialty, you will be able to download plans, instructions, and articles, and then order almost anything you can think of while sitting at a keyboard.

It is an exciting time to be in the hobby, and I hope you will try Indoor modeling and come fly with us.

Indoor FF Manufacturers and Suppliers: In the almost 20 years since Ron Williams’ lament that I included at the beginning of this article, quite a few brave souls have ventured into supplying the Indoor market.

At least two things have helped this along, the first of which is the increasing use of exotic, non-hobby-shop materials such as tungsten wire and boron and carbon fiber. Second is the explosion of email and webites, giving equal opportunities to modelers living anywhere on the globe.

SOURCES:

National Free Flight Society (NFFS)

www.freeflight.org

Science Olympiad

www.soinc.org

Technology Student Association

Indoor News and Views

Comments

Add new comment