Free-LAANC drone pilot

Written by Patrick Sherman Advanced Flight Technologies Column As seen in the July 2018 issue of Model Aviation.

As the UAS industry matures, it is becoming increasingly enmeshed in the broader aviation community. This trend is illustrated by the Low Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability (LAANC) program, which is opening the sky to drone pilots as never before. Not all advanced flight technology actually flies. Personnel and hardware on the ground allow the machines in the air to work safely and efficiently. Jetliners and air crews would be useless if not for the air traffic controllers, radar systems, and radio links—as well as the policies and procedures that guide them. Commercial drone operators are now starting to see a specialized infrastructure developing to support their activities, making it possible to fly in more locations and closer to airports, with real-time authorization.

Built for Drones

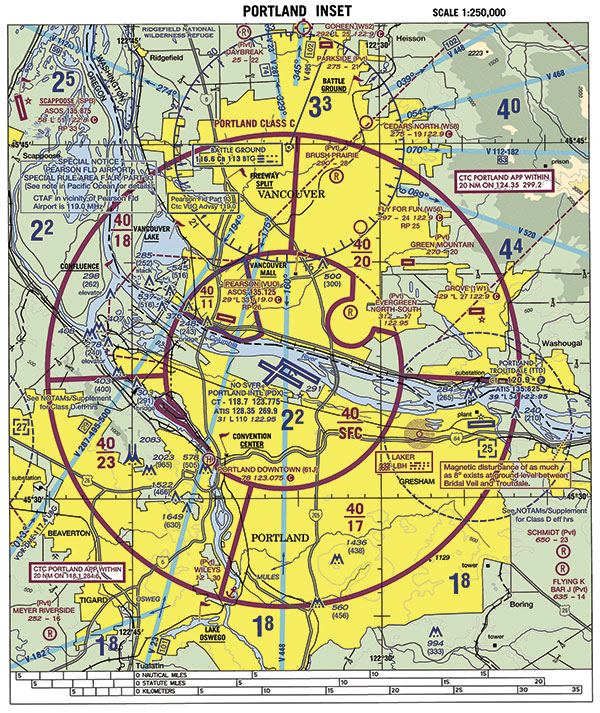

The FAA established LAANC to expedite the approval of commercial drone operations in controlled airspace while simultaneously providing a high-resolution map of locations where drones are able to operate at minimal risk to other air traffic. The National Airspace System (NAS) has served the aviation community well for many decades. Its most visible manifestations are the sectional charts that the FAA updates and publishes every six months, dividing the skies above our nation into different classes of air space: A, B, C, D, E, and G. It’s a world of upside-down wedding cakes—an analogy frequently used to explain how controlled airspace expands with altitude, in tiers, around controlled airports. The first problem is that, at the scale of drone operations, it is imprecise. For example, the lines printed on aeronautical charts to distinguish between controlled and uncontrolled airspace, when superimposed on the real world, are nearly half a mile wide. A Boeing 737 will cover that distance in roughly 3 seconds, but it could easily represent the entire area of operations for a drone pilot. The second problem is that when a manned aircraft pilot wants to enter controlled airspace, he or she makes a radio call to the control tower and gets an immediate answer. Before LAANC, a drone pilot who wanted to enter the same airspace sent an email to FAA headquarters in Washington, D.C., and, at best, could expect an answer in approximately a month.

The sectional chart has served as the manned aviator’s primary “road map for the sky” for decades, but its broad boundary lines and markings are too imprecise for drone flights, which might only travel a few hundred feet.

Delay Is Denial

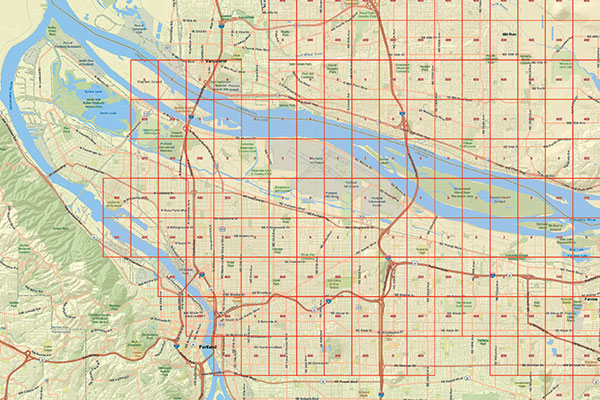

This simply isn’t practical in many situations, as I learned personally through a recent, heart-rending situation. During a national student walkout honoring the students and staff who were killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, a group of students in my hometown of Portland, Oregon, decided to lie down on the football field in the shape of the number 17—the number of people killed in the attack. They thought this silent demonstration would be best viewed from the air, so they contacted me about providing drone coverage for the event. Unfortunately, their school is located within the Class C airspace surrounding Portland International Airport. To be guaranteed permission to make that flight, I would have had to submit my request to the FAA before the tragedy in Florida. LAANC has already begun to make such conundrums a thing of the past by creating a system for drone pilots that closely resembles the resources and protocols that have been used for decades by manned aviation, but with a high-tech twist. The first part of this effort is what the FAA calls UAS Facility Maps (UASFMs). Throughout 2017, the agency worked with more than 500 airports across the country to conduct a detailed analysis of where drones could safely operate within controlled airspace. The FAA reasoned that just because you don’t want a Cessna 172 barreling through a particular patch of sky at 120 knots unannounced doesn’t mean that a drone couldn’t safely conduct a roof inspection while hovering 75 feet above ground level in that same area, provided air traffic control (ATC) is aware of it. To construct the UASFMs, the agency divided the area surrounding each airport into a grid of 1-mile squares and worked with local controllers and airport managers to determine how high a drone could safely fly within each of those squares. On the approach and departure routes, that altitude is zero. However, elsewhere within the airspace, that altitude rises to 100 feet, 200 feet, or even the 400-foot maximum established by Part 107 regulations.

To address the needs of commercial drone pilots operating in controlled airspace, the FAA has developed UAS Facility Maps for more than 500 airports across the US, showing altitudes where drones can fly without additional safety analysis, provided the pilots receive permission from ATC via the LAANC system.

Log On to the Sky

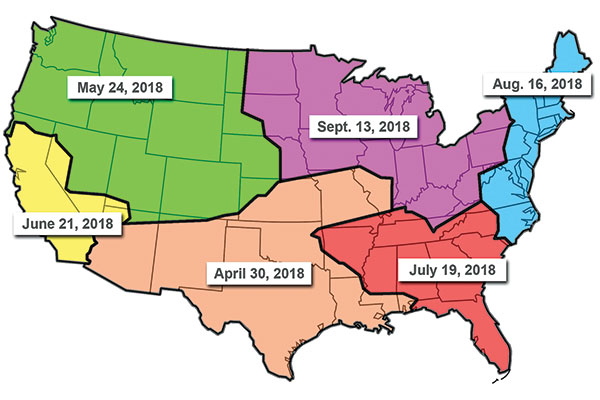

The altitudes indicated on the UASFMs do not give automatic permission for drone pilots to fly in those locations; they merely indicate where operations can occur without additional safety analysis. You still need authorization to enter that controlled airspace just as a manned aircraft pilot does. To facilitate this process, the FAA has partnered with the private sector to provide nearly real time approval for these requests. Presently, four companies provide this service: Skyward, Rockwell Collins, Project Wing, and AirMap. Known collectively as UAS Service Suppliers (USS), they are responsible for taking the UASFM data and building maps for their users, incorporating additional information such as Temporary Flight Restrictions and Notices to Airmen. Accessing the map provided by his or her USS, an individual pilot or commercial drone operator requests permission to fly using an interface such as a website or smartphone app. That request is then relayed through the FAA’s network to the local ATC, which has the option to approve or deny it. The whole process has the potential to work in nearly real time, as do requests from manned aircraft. For airports not covered by UASFMs, pilots can still seek approval directly from the FAA. This whole process has no bearing on hobbyists, who should continue to follow the long-established guidance: “Public Law requires hobbyist operating under the Special Rule for Model Aircraft (Section 336) to notify all airports within 5 miles of his or her flight/operation.” Sensitive to being accused of playing favorites among private companies, the FAA has already laid out a step-by-step process that will allow new vendors to join the ranks of approved USS providers.

Add new comment